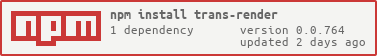

Package Exports

- trans-render

- trans-render/init.js

- trans-render/interpolate.js

- trans-render/repeatInit.js

- trans-render/update.js

This package does not declare an exports field, so the exports above have been automatically detected and optimized by JSPM instead. If any package subpath is missing, it is recommended to post an issue to the original package (trans-render) to support the "exports" field. If that is not possible, create a JSPM override to customize the exports field for this package.

Readme

trans-render

trans-render provides an alternative way of instantiating a template. It draws inspiration from the (least) popular features of xslt. Like xslt, trans-render performs transforms on elements by matching tests on elements. Whereas xslt uses xpath for its tests, trans-render uses css path tests via the element.matches() and element.querySelector() methods.

XSLT can take pure XML with no formatting instructions as its input. Generally speaking, the XML that XSLT acts on isn't a bunch of semantically meaningless div tags, but rather a nice semantic document, whose intrinsic structure is enough to go on, in order to formulate a "transform" that doesn't feel like a hack.

Likewise, with the advent of custom elements, the template markup will tend to be much more semantic, like XML. trans-render tries to rely as much as possible on this intrinisic semantic nature of the template markup, to give enough clues on how to fill in the needed "potholes" like textContent and property setting. But trans-render is completely extensible, so it can certainly accommodate custom markup (like string interpolation, or common binding attributes) by using additional, optional helper libraries.

This leaves the template markup quite pristine, but it does mean that the separation between the template and the binding instructions will tend to require looking in two places, rather than one. And if the template document structure changes, separate adjustments may needed to make the binding rules in sync. Much like how separate style rules would eed adjusting.

Advantages

By keeping the binding separate, the same template can thus be used to bind with different object structures.

Providing the binding transform in JS form inside the init function signature has the advantage that one can benefit from TypeScript typing of Custom and Native DOM elements with no additional IDE support.

Another advantage of separating the binding like this, is that one can insert comments, console.log's and/or breakpoints, in order to walk through the binding process.

For more musings on the question of what is this good for, please see the rambling section below.

Workflow

trans-render provides helper functions for cloning a template, and then walking through the DOM, applying rules in document order. Note that the document can grow, as processing takes place (due, for example, to cloning sub templates). It's critical, therefore, that the processing occur in a logical order, and that order is down the document tree. That way it is fine to append nodes before continuing processing.

For each matching element, after modifying the node, you can instruct the processor to move to the next element sibling and/or the first child of the current one, where processing can continue. You can also "cut to the chase" by "drilling" inside based on querySelector, but there's no going back to previous elements once that's done. The syntax for the third option is shown below for the simplest example. If you select the drill option, that trumps instructing trans-render to process the first child.

It is deeply unfortunate that the DOM Query Api doesn't provide a convenience function for finding the next sibling that matches a query, similar to querySelector. Just saying. But some support for "cutting to the chase" laterally is provided.

At this point, only a synchronous workflow is provided.

Syntax:

<template id="test">

<details>

...

<summary></summary>

...

</details>

</template>

<div id="target"></div>

<script type="module">

import { init } from '../init.js';

const model = {

summaryText: 'hello'

}

const Transform = {

details: {

summary: x => model.summaryText

}

};

init(sourceTemplate, { Transform }, target);

</script>Produces

<div id="target">

<details>

...

<summary>hello</summary>

...

</details>

</div>"target" is the HTML element we are populating. The transform matches can return a string, which will be used to set the textContent of the target. Or the transform can do its own manipulations on the target element, and then return an object specifying where to go next.

Note the unusual casing, in the JavaScript arena: property Transform uses a capital T. As we will see, this pattern is to allow the interpreter to distinguish between css matches and a "NextStep" JS object.

Use Case 1: Applying the DRY principle to (post) punk rock lyrics

Example 1a (only viewable at webcomponents.org )

Note the transform rule above (if viewed from webcomponents.org):

Transform: {

'*': x => ({

Select: '*'

}),- is a match for all css elements. What this is saying is "for any element regardless of css characters, continue processing its first child (Select => querySelector). This, combined with the default setting to match all the next siblings means that, for a "sparse" template with very few pockets of dynamic data, you will be doing a lot more processing than needed. But for initial, pre-optimization work, this transform rule can be a convenient way to get things done more quickly.

[More documentation to follow]

Ramblings From the Department of Faulty Analogies

When defining an HTML based user interface, the question arises whether styles should be inlined in the markup or kept separate in style tags and/or CSS files.

The ability to keep the styles separate from the HTML does not invalidate support for inline styles. The browser supports both, and probably always will.

Likewise, arguing for the benefits of this library is not in any way meant to disparage the usefulness of the current prevailing orthodoxy of including the binding / formatting instructions in the markup. I would be delighted to see the template instantiation proposal, with support for inline binding, added to the arsenal of tools developers could use. Should that proposal come to fruition, this library, hovering under 1KB, would be in competition with one that is 0KB, with the full backing / optimization work of Chrome, Safari, Firefox. Why would anyone use this library then?

A question in my mind, is how does this rendering approach fit in with web components (I'm going to take a leap here and assume that HTML Modules / Imports in some form makes it into browsers, even though I think the discussion still has some relevance without that).

I think this alternative approach can provide value, in that the binding rules are data elements. A web component can be based on one main template, but which requires inserting other satellite templates (repeatedly). It can then define a base binding, which extending web components or even end consumers can then extend and/or override.

Adding the ability for downstream consumers to override "sub templates" should probably come towards the end of development, together with optimizing, as it could break up the rhythm somewhat in following along the flow of the markup. Nevertheless, in the markup below, based from this custom element we provide suggestions for how this can be done.

The web component needs to display two nested lists inside a main component -- the list of web components contained inside an npm package, and for each web component, a list of the attributes. It is natural to separate each list container into a sub template:

const attribTemplate = createTemplate(/* html */ `

<dt></dt><dd></dd>

`);

const WCInfoTemplate = createTemplate(/* html */ `

<section class="WCInfo card">

<header>

<div class="WCLabel"></div>

<div class="WCDesc"></div>

</header>

<details>

<summary>attributes</summary>

<dl></dl>

</details>

</section>`);

const mainTemplate = createTemplate(/* html */ `

<header>

<mark></mark>

<nav>

<a target="_blank">⚙️</a>

</nav>

</header>

<main></main>

`);NB The syntax above will look much cleaner when HTML Modules are a thing.

The most "readable" binding is one which follows the structure of the output:

{

Transform: {

header: {

mark: x => this.packageName,

nav: {

a: ({ target }) => {

(target as HTMLAnchorElement).href = this._href!;

}

}

} as TransformRules,

main: ({ target }) => {

const tags = this.viewModel.tags;

repeatInit(tags.length, WCInfoTemplate, target);

return {

section: ({ idx }) => ({

header: {

".WCLabel": x => tags[idx].label,

".WCDesc": ({ target }) => {

target.innerHTML = tags[idx].description;

}

},

details: {

dl: ({ target }) => {

const attrbs = tags[idx].attributes;

if (!attrbs) return;

repeatInit(attrbs.length, attribTemplate, target);

return {

dt: ({ idx }) => attrbs[Math.floor(idx / 2)].label,

dd: ({ idx }) => attrbs[Math.floor(idx / 2)].description

};

}

}

})

};

}

} as TransformRules

};

However, this would be difficult for extending or consuming components to finesse (if say they want to bind some additional information inside one of the existing tags).

The rule of thumb I suggest is to break things down by template, thusly:

export const subTemplates = {

attribTransform:'attribTransform',

WCInfo: 'WCInfo'

}

export class WCInfoBase extends XtalElement<WCSuiteInfo> {

_renderContext: RenderContext = {

init: init,

refs:{

[subTemplates.attribTransform]: (attrbs: AttribInfo[]) => ({

dt: ({ idx }) => attrbs[Math.floor(idx / 2)].label,

dd: ({ idx }) => attrbs[Math.floor(idx / 2)].description

} as TransformRules),

[subTemplates.WCInfo]: (tags: WCInfo[], idx: number) =>({

header: {

".WCLabel": x => tags[idx].label,

".WCDesc": ({ target }) => {

target.innerHTML = tags[idx].description;

}

},

details: {

dl: ({ target, ctx }) => {

const attrbs = tags[idx].attributes;

if (!attrbs) return;

repeatInit(attrbs.length, attribTemplate, target);

return ctx.refs;

}

}

} as TransformRules)

},

Transform: {

header: {

mark: x => this.packageName,

nav: {

a: ({ target }) => {

(target as HTMLAnchorElement).href = this._href!;

}

}

} as TransformRules,

main: ({ target }) => {

const tags = this.viewModel.tags;

repeatInit(tags.length, WCInfoTemplate, target);

return ({

section: ({ idx, ctx }) => ctx.refs,

})

}

}

};